By Busi Ntsele

The field visit to Meraka Cultural Village reignited my passion for advocacy and transformation. When we arrived at Meraka, with our music playing from a small speaker connected to the phone, Mme Sebabatso came out in full smiles, moving to the beat, and teaching us how dance looked in the golden old days.

We were all amazed at how she went into the full rhythm, patting her body and swinging her arms at the same time. She called this dance move the Phatha Phatha meaning touch, touch. “Phatha Phatha was a hit in my time,” she told us.

This day was supposed to be about research questions and structured interviews on engaged scholarship, but that was soon forgotten. Instead, Mme Sebabatso welcomed us with dance and the news that a group of students from UFS would be arriving soon. She let us know that we would need to work as a team as we would be learning together. Indeed, before I knew it, the place was buzzing with laughter, noise, and introductions. Once the introductions were done, we all dived into learning how to build an indigenous shelter. We began the process by collecting cow dung, horse manure, and straw from a nearby farm in a wheelbarrow. Meanwhile, others were collecting bottles, boxes, sand, and water, and pushing tires around. These were the main tools used to create a building foundation like those in the Meraka cultural village.

Coming Together: Where Culture Meets Education

Meraka means coming together. The cultural village is a space where culture meets education. It was started by Mme Sebabatso who later partnered with the University of the Free State (UFS). Meraka then became a creative way of bringing together students, academics, and people from the surrounding community to learn about culture whilst also learning to build indigenous shelters. Such shelters are eco-friendly, low cost, and adaptable for use as an alternative form of housing.

The Meraka project is an example of one of the ways UFS is doing engaged scholarship. The university supports the community with human and financial resources. Mme Sebabatso trains students on indigenous knowledge systems, and, for their part, the students get to be part of the team building shelters at the cultural village.

Informal Settlements

In all my 4 years of living in Bloemfontein, I had never been to an informal settlement. One day, we travelled as a group to look for bottles in a dump site close to an informal settlement near Bloemfontein. We passed through the settlement where poor people had found unoccupied land and started using anything they could find to make shelter, from corrugated iron, plastic, to card boxes. Seeing the conditions made my heart sank and what started as excitement to hunt for building materials was quickly erased by the unpleasant welcome of a foul odor. The odor was the result of the dump site. Informal settlements have no formal ways of waste disposal in place. There are no formal roads either. All we could see were small mkhukus[1] occupied by Black people. These were my people still living in shacks in the new democratic South Africa.

Something in me shifted tremendously that day from someone who just wanted to do research on people to someone who wanted to do research with my people. So, I started seeing Meraka as an alternative to my people’s living conditions instead of the shacks.

De-Valuing Indigenous Knowledge

A journey that was meant to give me answers for my PhD research question, what is the engaged scholarship and how is it practised at UFS, turned into more questions and a hunger for social justice. At the dump site, we collected bottles and plastics for building, but all I could think about was, how can South Africans still be living under such living conditions 25 years post-independence?

As we drove off, little children with big smiles were waving and shouting nangu mlungu, mlungu in excitement. Which meant white people in the area. It pained me to see that these young children thought these white people were there to save them from harsh conditions. I began to have childhood flashbacks of when white people would come into our community and take pictures of us in exchange for sweets or coins. This created the impression that white people were there for us.

This train of thought led me to remember what it was like as a child growing up in the diaspora in the Kingdom of Eswatini. I grew up having dinner in a stick and mud hut which was built by my grandfather years before I was born. My grandfather passed away in January 1980 just before I was born. The hut was a legacy that he left behind for us. I have fond memories of having dinner and playing poker in this kitchen. For the longest time, our neighbours had the same huts. However, my generation started thinking of the huts as barbaric and uncivilized and demolished them to replace them with brick ones. By the early 1990s, we were constantly teased for still having such a hut, and I came to hate it myself.

In 2005, I began working and had our mud hut demolished to have a new brick one built in its place. Being confronted with the informal settlement made me look back and realise just how strong our mud hut had been back then. In today’s terms, the strength of the hut made it climate resilient. The mud hut had been built by my grandfather who had neither formal education and nor was he an architect, but using indigenous wisdom and experience he created a house that had stood the test of floods, winds, and storms.

Exclusionary Building Codes

This reflection made me even more passionate to advocate for changes in the South African building code policy. I was confronted with the discomfort of asking myself what my role was as an engaged scholar in this project. I began reimagining a future where together we would collect all the waste and dump sites would be clean because we would recycle the waste for building purposes. I re-imagined a world where policymakers, scholars, students, and communities would come together to build the South Africa that we dreamt of pre-1994. A South Africa where Black people had decent housing like everybody else.

I found myself wondering, how is it possible that South African housing codes remain unchanged in a country that has vast inequalities that are manifesting themselves in issues such as lack of housing? If the voices of the community could be heard and their narrative made inclusive, then the community would have decent housing and that would improve quality of life.

For years communities such as Meraka have been advocating for the possibility of making indigenous housing permissible. Currently, it is impossible to certify a mud hut safe without paying ridiculous amounts of money for certification by a professional architect.

[1] Mkhukhu: is a word for shack used by Black people in South Africa.

The Single Story Multiplies

For me what started as a lonely and stressful PhD journey to visit one of the university’s engagement programmes became a journey of advocacy. I went into the project thinking I was going to research and get answers, but I found a home. I was reminded of Chimamanda’s concept of the danger of a single story[1] because I had always read about and imagined poor communities as vulnerable and lacking empowerment. Hence, I had envisioned myself as empowering people through my research and sharing its findings. However, it turned out that the learning was reciprocal and the relations were mutual in the process of co-creating knowledge at Meraka. The picture of vulnerable people I had profiled did not exist in real life. They were prisoners of a single story of loss and poverty. In Meraka, the singularity of that story was broken when I saw that the people were welcoming, happy, strong, wise, and organically driven by a common goal, not timelines and the pressure to excel.

Building together and learning indigenous methodologies was not only empowering but it also became a space of escape from my life worries. Meraka was not an ordinary building site, but therapy. I benefited more in the community than I had ever done in class. The special setting at Meraka had a healing effect on me after years of PhD stress. The morning routine would always start with an interesting drive, beautiful music, and laughter. We would get to the site and receive hugs and tea from Mme Sebabatso. The day would start with tire pounding and bricklaying using mud and cow dung. We would sing and listen to music from our phones stopping occasionally to dance, take pictures or have an open mic poetry session. Lunch was always a vegetarian soup made with love from Mme’s kitchen. Then we would take turns cleaning up and go back to the building. At the end of each day, we would gather around and reflect on the day, what we loved and could improve, and take home points. This was a bonding session that allowed us to hear individual voices, thoughts, fears, accomplishments, and aspirations. Meraka was not what I had imagined.

I Am Because You Are

I had intended to do my PHD interviews at this time with all the students but instead, it became a reconstruction site of my role as an engaged scholar. I had a chance to deconstruct my narrative of vulnerable people told from the lens of poverty because the wealth and richness of the experience were more meaningful. I did not get the answers I was curious about, but the research led me to rethink the ways in which I could co-create with the community. I reflected on how joining the re-future advocacy group had become an opportunity grounded in teamwork, honest engagements, shared responsibility, and mutually beneficial partnerships.

Every day we would sit outside and listen to each person’s dream of what the next step should be if our ideas were to really be transformative. Sometimes people in the community would be so excited and talk continuously but Mme Sebabatso would ensure that everyone had a chance to speak. Often what makes co-creation difficult is that scholars we are not used to listening to the voices of the people actively without the pressure of doing research. I was privileged to be part of the process because I got to listen attentively. I took notes and later requested individual interviews with some of the students. At the end my biggest lesson was that communities are created through working together and there is power in solidarity.

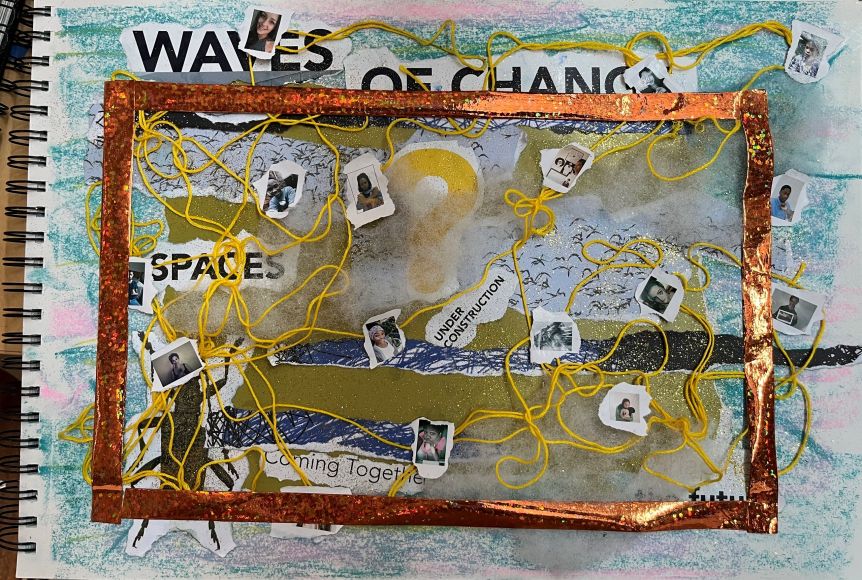

As a result of seeing value in indigenous building methodologies, I ended up joining the team of Meraka Re-Future Change Agents. The Re-Future Change Agents is a group of students and academics that aim to support the Meraka building project by challenging South African housing policy. The project is inspired by regenerative design and arts-based research methodologies. The group consists of students from UFS and Hasselt University in Belgium who took part in the Meraka building project in 2019.

We strongly believe that together with Mme Sebabatso we can use the Meraka story to influence policy. This sort of co-creation requires a lot from us, it’s hard work and it takes time for the communities to trust us before we can hear their voices, but it’s not impossible.

Bishop Tutu was vocal about believing that we are not made to live alone as individuals. God has called us to live in love and relationship with each other. Meraka embodies the values of ‘’umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’’ as he often called this notion of togetherness.[2] We see this through the value of engaged scholarship and meaningful interactions.

[1] “The Danger of a Single Story” is a TED Talk given by Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at TEDGlobal 2009. In the speech, Adichie reflects on the power of story and the danger of believing one story about a region or group instead of acknowledging the complexity of many stories. https://youtu.be/D9Ihs241zeg