I have always loved working alone. Having time to organize thoughts, write them up, correct and polish my expressions until they appear of sufficient quality to be shared with others. Clearer, brighter and better structured than if I had to shape them in the immediateness of face to face interaction…

The quickness of immediate interchange often feels scary to me. Being able to escape it is, no doubt, a privilege of the researcher, which becomes even more evident in this bizarre time of forced isolation.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, all of us are confined to our homes. While many others are forced into an unnatural limitation of their productivity, a vital part of our work apparently can continue perfectly fine in the solitude of our home desks. In reshaping our daily work, we can easily reach back to archetypal images of the researcher that are still present in our imaginary, despite recurrent critiques of it: The lone thinker, the individual creative spirit of the writer. Of course, an ethnographer cannot do her work without immersing herself in the messy field, walking along and participating. And yes, a researcher’s job is to listen to people, ask questions and enter into dialogue. But after this period, her own voice takes shape in articles and papers that are born in the controlled laboratory of solitude.

And so, in a small spot of my home that is shielded from toys, daily noises of family interactions and troubling news channels, I have recreated a small nostalgic corner, made of books, shelves and writing. Here my respondents, companions of earlier conversations, come to life as magical characters in a play that I, the sole director, can shape as I choose.

From this unnaturally shielded space I want to travel back a few weeks, to the life that lies behind us, observing the passage from intensive interaction, to that of confined interpretative work. And reflect on the importance of personal exchange for the type of work we aim at in the project Engaged Scholarship and Narratives of Change.

Even solitary thought is a social game

This image of the lone writer has something in it, that contradicts the way I have learned to look at research and scientific production from the beginning of my academic training. As a student, I grew up with Wittgenstein’s writings, that functioned as one of the essential sources for the later development of social constructionist worldviews and epistemologies. Immersed in these texts I absorbed the basic philosophical premise that all ability to think and express thoughts in language is essentially social. ‘Language games’, including the production of scientific analysis and scientific discourse, are essentially social games, rooted in relations with others. This is true even at those moments in which we borrow this space for ourselves and play these games ‘solo’, thinking, writing… moments in which we use language in a ‘private dialogue’, and the relation with our listeners becomes imagined.

The idea itself of solitary production echoes the illusion of the ‘escape from plurality’, like Hannah Arendt explains in her essay Philosophy and Politics (p. 438), in which she shows that thought itself always has a dialogical form.

So, while real or imagined others are always part of what we produce, it is essential to reflect on the type of social relations that are implied in this production: how others enter this space, who enters it, who controls it, what power relations exist in it and are reproduced in it.

In our project, we focus exactly on the relationships that exist between those involved in the production from a range of different positions (researcher, ‘research object’, active participant, supervisor, funding agency, etc.) and how we can work towards relationships that are respectful, regenerative and reciprocal.

Reflecting on power through co-creation

Engaged Scholarship and Narratives of Change aims at discovering conditions through which knowledge co-creation can contribute to create reflective spaces and structures that enable the inclusion of refugees in different societies. The project invites us daily to reflect critically on how knowledge production can either reproduce, resist or change tacit exclusionary mechanisms. Or how it can be complicit in sustaining images that dehumanize migrants and refugees, constructing them as helpless and dependent people, as essentially different Others, or as threats. Or how, at the other side, it can uncover personal stories that trigger reflection and can even transform people’s lives.

Co-creation is an essential notion in this project. This means aiming at connecting knowledge from different positions and creating sources of access for active knowledge production for those who are often only involved as ‘research objects’. In this type of collaborations lies the potential for research to become a source of epistemic resistance: creating knowledge that contributes to undermine and change oppressive discursive and normative structures (see Medina 2013).

‘Being there’ through art based research

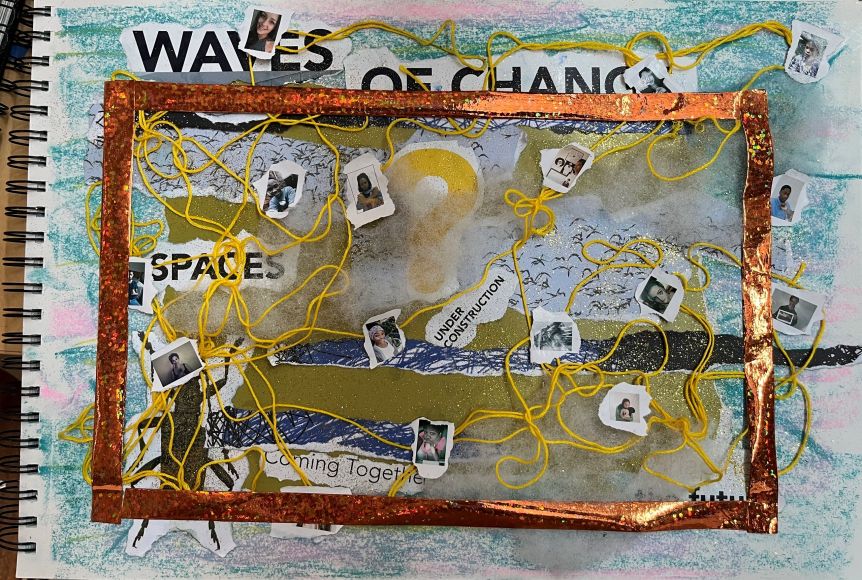

When the COVID-19 crisis caught us, our project was entering an exciting stage. Two of our researchers had left for their fieldwork in South Africa and California, and in the Netherlands, we had just started the cooperation with different artists. Our last meeting in person, was one in which we enthusiastically discussed plans for immersive storytelling workshops based on visual and performative games. PhD candidate Maria Rast would shape them together with theatre maker Petra Ardai, in order to collect stories and experiences of refugees that participated in engaged scholarship projects.

Using creative, arts-based research methods is a way to create alternative imaginations and to unlock the contribution of voices that might not fit existing frameworks.

But also to create a mutually empowering space, in which mirrored reflections can shed new light on the processes of exclusion and inclusion to which we all contribute, whether consciously or not. Discovering those processes thorough de-colonizing reflections often involves friction or emotional experiences of discomfort. Creating an emotional common ground, a space for shared emotions, is helpful for this experience of discomfort to become a cognitive resource. Because it allows to explore our own position, starting from what we feel and the immediate intuitions we have, by listening to experiences of others.

And so, during the meeting, Petra challenged us to become fully part of this shared space. No difference should be made between our involvement and that of participants. We should share our own stories, our own personal struggles and turning points, our own trajectories.

The smells and colours of our own lives would be as relevant, in the shared space of creative production, as that of the refugee participants. This demand by the artist, struck me as a thought-provoking call, pointing to an issue that seems underexplored in academic debates about collaborative research – without disregarding the extensive work on ‘positionality’ carried out within feminist, queer and post-colonial studies.

A beautiful special issue on Intimacy in research, by Mariam Fraser and Nirmal Puwar (2008) points at exactly this lacuna in academic research, claiming that the intimacy and physicality involved in the research experience should not just be polished away, but become a source of knowledge itself. Especially in co-creative research settings, it is specifically the interactive nature of this shared intimate space that becomes crucial. And in this sense, there is an important difference between ‘imagined intimacies’ (as in some of the cases described in the special issue, where authors describe intimate relations with people that lived in different centuries and even with the brain of a dead person), and the real-life entanglement of emotional connections and interactions that develop between researchers and participants. That is to say: the creation of intimate spaces in which participants can actually resist and counter our interpretations. Taking serious the idea that knowledge production is a relational field, the emotional aspect of this relation is an integral part of our methodology (see also the beautiful idea of Corazonar, introduced to us by Mimi Ocadiz).

“Who are you?”

It is undeniable that stories by participants (or researchers) with experiences of marginality and exclusion have a very specific and irreplaceable value, as do stories of strength and resourcefulness that have been made invisible by dominant discourses of lack.

Experiences and perspectives from the margin are essential to uncover mechanisms of exclusion. But that does not mean that in the relational sphere, in the encounter between participants and researchers (whether or not we have relevant experiences of exclusion or marginalisation), that our personal narrative presence is irrelevant.

Reviving the sharp words with which a particularly critical young man that I wanted to interview once addressed me: “But you, who are asking me these questions, who are you?” The question is a rightful one. It touches upon the issue of legitimacy: When can a researcher, who does not share certain experiences or social position with participants, be seen as a legitimate collector and interpreter of their experience? What degree of active engagement in the endeavours of participants is needed, in order to pursue equality and reciprocity in the research setting? Finding balanced answers to these questions is part of defining and understanding ‘who we are’ in relation to the people we involve and the field we are involved with as researchers. But in co-creative research settings, I believe, ‘who are you?’ becomes also a bare call to self-disclosure and vulnerability.

The self-disclosure I am envisioning involves not only parts of our personal story, but also our agenda as researchers, our struggles, our gains, and the theoretical and methodological choices we make.

As a white researcher, born in Europe, involved with research on migration and inclusion-exclusion, I am trained to reflect mostly on the limitations of my positionality, as something that should be acknowledged in methodology chapters. But for the other, the participant or co-creator, who we (researchers) are is an important part of the reflective relation that we want to create. In a recent participatory project with social workers and youth of migrant descent in Amsterdam, I experienced this vividly. Some of the young people involved in the research were connected with a community theatre project, which professionals took as starting point to shape encounters and conversations about the lives of youngsters and their expectations.

During a symposium which reunited the youngsters and professionals involved, I chose to share a very personal field note. There, I narrated my feelings when seeing the theatre production. I shared how these were rooted in my own background and story and how, departing from these emotions, I had started making sense of the experiences that were conveyed in the play. This exercise felt extremely vulnerable, but was very warmly welcomed by participants. The responses and reactions that I got from research participants to my own ‘performance’ – which could nearly be seen as a form of experiential theatre itself – became some of the most insightful pieces of my research material.

‘Cycles of interpretation’

Returning to my isolated desk, in the time of the COVID-19 crisis. I am glad to be able to listen to the recorded voices of my research participants. I enjoy their sound and the memories of our gatherings, in a time in which confinement has made care free being together a chimera. I am also somehow grateful for this unusual time I can spend on writing.

However, in absence of this crisis, today I would be meeting several of the people that I am listening to in a workshop organised by the social work professionals. Their mere presence, the physical encounter between us, would keep shaping our relation, and our shared imagination about the research topic.

Since, as Medina (2013) describes, ‘perspectives afforded by our social positionality’ establish ‘an intimate connection between our sensibilities and our cognitive potential’, intimate encounters between people with different positionalities shape our epistemic sensitivities, through which we discover both ourselves and ‘the other’ (Medina 2013, p 17).

In earlier work, I described a co-creative methodology of analysis, in which sharing interpretations of data with participants prompts reflective dialogues between participants from different positions and researchers, which creates new interpretations (Ponzoni 2015). These ‘cycles of interpretation’, as I called them, furthered both the knowledge of participants, as well as my own.

Research in a time of caring

Through the project Engaged Scholarship and Narratives of Change I would like to explore further how emotional and personal connections can contribute to create shared reflective spaces which are both ‘safe’ and ‘daring’. The story of ‘Sarah’ (Ghorashi and Ponzoni 2014), which became exemplary of the narratives of change that we hope to uncover in this project, was born in exactly such a space.

The ability to establish open, vulnerable and also caring relationships might be an important condition for these spaces to come into existence.

In that sense, the present crisis might also contribute to creating different kinds of dialogues that, while distanced, are centred on empathy, caring and on a shared sense of vulnerability.

References

Arendt, H. (2004) Philosophy and Politics. Social Research: An international Quarterly, 71(3), pp 427-454

Ghorashi, H., & Ponzoni, E. (2014). Reviving agency: Taking time and making space for rethinking diversity and inclusion. European Journal of Social Work, 17(2), 161-174.

Fraser, M. and N. Puwar (2008). ‘Introduction: intimacy in research’, History of the Human Sciences, 21, pp. 1–16.

Medina, J. (2013). The epistemology of resistance: Gender and racial oppression, epistemic injustice, and the social imagination. Oxford University Press.

Ponzoni, E. (2016). Windows of understanding: broadening access to knowledge production through participatory action research. Qualitative Research, 16(5), 557-574.