Immigrants experience many different forms of exclusion. Sometimes, the sources of exclusion are harsh and blatant, such as the discrimination and hatred that undocumented immigrants experience from being called “occupiers,” “criminals,” or “rapists.” At other times, these sources of exclusion are more subtle, such as when everybody agrees that immigrants should conform to the mainstream culture of the country of settlement at the expense of their own cultural and personal identities.

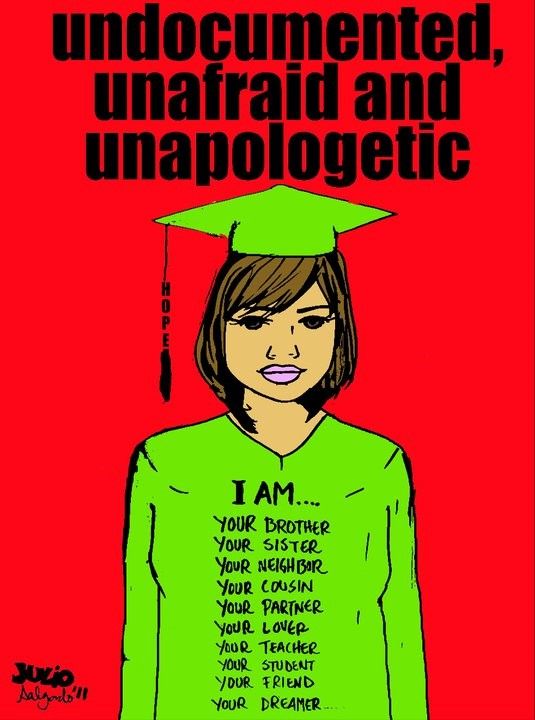

Over the past two decades in the United States, undocumented youths emphasized their social and cultural adaptation to mainstream American life. They did this because they wanted to be recognized as human beings deserving of citizenship rights. It was a deliberate political strategy. Because of their advocacy and political mobilization for the Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, this group of undocumented immigrants became commonly known as the Dreamers. The bright colored cap and gown became their collective symbol, signaling their social position as students.

The good-bad immigrant

The political strategy of the Dreamers rested on showing they deserved to be US citizens by stressing their virtues and downplaying more stigmatized parts of their identities. They did so by emphasizing three essential characteristics of the Dreamers. First, they were “real Americans” who spoke perfect English and enjoyed typical American things like baseball. Second, they were excellent students that contribute to society, because they were “the best and the brightest of their generation.” Third, they were not to blame for their undocumented legal status, because they crossed the border “not by fault of their own.”

This strategy worked and gave undocumented youths a positive public image and collective identity as Dreamers. However, some people felt that this typical Dreamer story created a split between undocumented students and their undocumented parents. They argued that it created a division between supposedly “deserving” immigrants, such as undocumented students, and supposedly “undeserving” immigrants, such as undocumented workers.

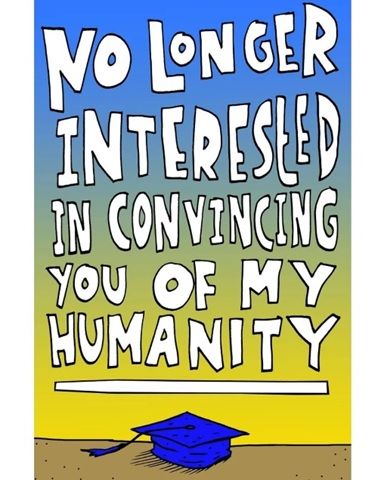

Undocumented youths then reflected on the unintended effects of their political strategy and many no longer wanted to be called Dreamers. They did not want to contribute to the social exclusion and stigmatization of their undocumented parents, friends, family, and community members. Consequently, many people who used to identify as Dreamers started using their strong public voice to fight for the rights and inclusion of all 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States.

For the past eight years, I have been conducting research on undocumented youth activists in the city of Los Angeles. In one of my interviews with Manuela, a queer Latinx undocumented youth activist that came to the US from Mexico City at the age of 7, she discussed how her attitude about the Dreamers changed. Manuela:

"I definitely don’t identify as a Dreamer and at some point, I did. Because I was a student, right, because I didn’t have a criminal background. I distanced myself from the larger immigrant population, because I felt like I was different. And I don’t feel that way at all. I’m against folks feeling like the good-bad immigrant. I don’t long to be an American. I mean, I have a lot of grievances and a lot to say about America and I don’t feel that that’s something I want to strive to be. And I think at some point I did."

Manuela now feels that she has the right to be critical of America. Because the Dreamers became a political force to be reckoned with, she now feels that she has the right not to want to be an American.

Love it or leave it

However, many immigrants, especially refugees and undocumented immigrants, feel that they do not have the luxury to be critical of the country of settlement. They feel that the local population expects them to be grateful and adapt to the existing culture, even when they do not agree with local cultural customs and values. “Love it or leave it,” is what locals say. But, isn’t critique also a sign of love? It’s precisely because you love the country that you want to put in the effort to critique and improve it.

This attitude is one of the subtle forms of exclusion that immigrants have to deal with on a daily basis. It signals to immigrants that they don’t really belong. You are only allowed to be critical of the national culture if you are from there, or so the reasoning goes. “Never talk religion or politics with the locals,” my grandmother used to say before we would go abroad. “And don’t talk negatively about their cuisine,” she would add.

Exclusionary language, such as “love it or leave it” thus tells immigrants that they are not at home in their country of settlement. Instead, immigrants are considered to be guests, and guests are expected to abide by the set rules of the host. Guests need to clean up after themselves. They need to say please and thank you. And “guests are like fish, after three days they stink.” Or so the European saying goes. Thus, treating immigrants as guests that will soon “go back to their own country” does not suffice.

But when we follow the hospitality metaphor, we see that there are also expectations of the host. A good host is generous and welcoming. “A merry host makes merry guests,” the English say. A host needs to be a guide to its guests, but also needs to give them some alone time. A good host understands that guests also have their own routines and preferences. Even the bible reads: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Hebrews 13:2).

Victimization

There are even subtler forms of exclusion that are more difficult to spot. An example of this can be found in the common occurrence of people treating refugees and other immigrants as victims and taking pity on them. This takes away their personal power, or agency as social scientists like to call it. Manuela also says something about this:

"And I don’t want pity. I don’t want people to feel like, “Oh, poor undocumented girl.” And I think being young had a lot of that, you know, having people feel pity for us, because we were so great, going to school, doing all these things and having all these hurdles and you managed to overcome them. Now, I don’t want that. I don’t like that. I don’t want to feel like I need any help, that I’m helpless."

While it might be essential to recognize that refugees and undocumented immigrants have experienced loss, trauma, and disruption, it can be terribly patronizing to consider them helpless. It is not only degrading, but also very debilitating and unproductive. If you only perceive people from this perspective or discourse of lack, then you will miss out on people’s resources, skills, potential, and contributions. By only focusing on how refugees and undocumented immigrants need the help of the country of settlement, you miss out on how they might help their country of settlement.

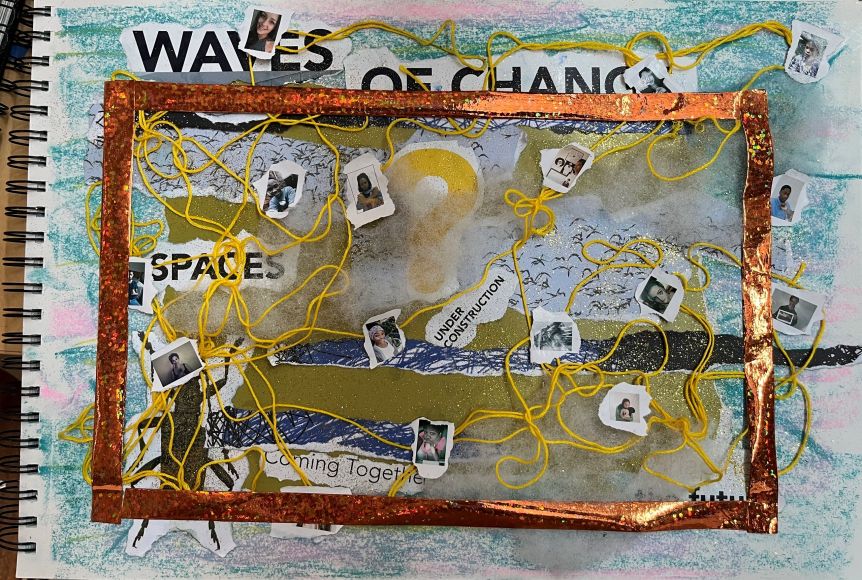

Fighting these subtle and normalized forms of exclusion and seeing immigrants in their full humanity and power, is what our research project on Engaged Scholarship and Narratives of Change is all about. Our research is about uncovering stories with the capacity to transform people’s lives and fully include refugees in our diverse societies. As a postdoctoral researcher, I seek to co-create new ways in which academia can contribute to the actual inclusion of refugees.

This project invites refugees and engaged scholars in the Netherlands, South Africa, and the United States to identify normalized forms of exclusion, such as the abovementioned pressures to assimilate and processes of victimization. It then asks other stakeholders in those three countries to collectively reflect on these stories and experiences of exclusion for the purpose of co-creating and imagining alternative pathways to inclusion. Will you join our endeavor?

Illustrations/artwork made by undocumented artist and activist Julio Salgado. Retrieved on 29 December 2019 from: https://juliosalgadoart.com/.