We are honored to welcome Phoebe to our team! She is an African feminist scholar, a black academic, a nomadic subject, and a great friend who fights for social justice. With a vast experience in community engagement and art practices, Phoebe has now joined us as a co-promoter for the South African context and critical supporter for the overall project. Read Mimi’s interview with Phoebe to know more about her background, her experience with the FeesMustFall movement, and her moving engagement with marginalized communities in South Africa.

Welcome Phoebe, thank for being our guest in this podcast. Can you introduce yourself in your own words?

I’m Phoebe Kisubi Mbasalaki, I refer to myself as a nomadic subject, I was originally born in Uganda but have lived on several continents. I recently moved to the University of Essex where I’m a lecturer at the Department of Sociology, before that I was based in South Africa. My research focuses on gender and sexuality and it’s intersections with race and class.

You mention South Africa, and it’s a country you describe as your home. What is it in South Africa that attracts you so much, that always brings you back there?

The starting point would be doing my bachelor there. This was both being equipped but also a becoming of a political subject, being conscious and getting to know the South African context in terms of colonialism and apartheid. I grew up watching this in television but living there opened up these intersections between race, class and gender, so I became politically aware as a student in that space. That awareness led me to seek social justice and I think that awakening led me to feel at home in South Africa.

Since then, all my academic work has been rooted in social justice. That’s the strong connection: South Africa is where I became awoken!

And I also studied at the University of Cape Town, which is a beautiful city! Who would not love to wake up at the mountain or the sea? I also got fully introduced to enjoyment in terms of food and wine. I also have really strong interpersonal connections at the university from my student days, many of whom I still connect with now. Many of them are still in Cape Town and are doing really amazing transformative work at the university, and were really influential in my progress as an academic. I’m still connected to them while I work in different places, every time I go back there, I feel at home because of these bonds. I have my South African family as I called them.

In the context of South Africa, a movement that has been crucial is FeesMustFall, that highlighted an ongoing issue: undoing the injustice of apartheid and colonialism. How do you experienced the movement?

I went to South Africa in 2014 to collect my doctoral thesis data, and it was very much connected to the University of Cape Town and the movement was already bubbling by then. I remember I had several conversation with my connections.

I actually lived with one of them while I was collecting my data and she is a professor at the University of Cape Town. She taught me in my undergraduate. Our conversations were mainly about how black lecturers and blacks student always felt like they don’t belong. For instance I didn’t see myself reflected in the material taught, and that hadn’t changed ten years later, when I came back for my doctoral studies. Although, she did became a full professor and has done great work towards transforming the university. But the more black students entered, the more they felt they didn’t belong. They saw the University of Cape Town as an space with many layers of elitism, one of them being tuition, the materials being taught rooted in Western epistemologies and with no connection whatsoever with indigenous knowledge. So I arrived in Utrecht after being in South Africa, and then the movement started. And I was so emotional! Even if I was far away, I felt so connected.

So you were abroad when the movement actually took place, but then you came back to develop a new project with sex workers, a group that has been historically marginalized. Did you noticed any change? I know decolonization is a process, but after FeesMustFall, what happened?

After that huge disruptor on trying to rethink what the university is, I had this desire to return to South Africa and be part of it. Although I was already part of it, I wanted to be at the heart of it. So when this postdoc opportunity came around I embraced it and I ended up in the African Gender Institute. And I arrived there with so much energy! Because you know how social movements take so much energy, when you push against institutions, power reasserts itself and it requires extra work. When I came back many of my friends and colleagues were exhausted, and there I was, full with energy! I wanted to do something! I joined the Black Academic Caucus and I wanted to do everything!

But tracking back to your question on shifts and changes, there was work done in the way they taught, which led to this eruption, but pushing the institution itself on a macro level only happened after the FeesMustFall. The real push for change in policies around the curricula happened after this shift. What kind of curricula is thought in this university where there are diverse students, that is not only directed to the white male, but that is also inclusive of the others. So these transformative policies were born then and now there are these different transformation positions at the university. Positions like the Vice-chancellor for Transformation, also Deputy Dean of transformation, and various other positions. But you know how power works in co-opting, so after this transformation, there are walls that are built.

And within the African Gender Institute were I was based there was a deep introspection about what African feminism really is, what a curricula that embraces this looks like. There was a massive change in the curricula, and the kind of research done in deep cognizance of inequalities but also the communities where the university is based. Cape Town is a divided city clearly around race and class. The Grace project where I ended up working was really cognizant about the university being in service to the communities and challenge separations. That means recognizing the histories that have produced bodies on the margins, colonization and coloniality and how this manifest in contemporary South Africa.

We paid attention to them and worked within cross-disciplinarity, not only at the university but also with institutions that do grass-root work. That is how this collaboration started between the African Gender Institute, the Centre for Theatre and Performance Studies and the NGO the Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Task force (SWEAT), and worked with a group of sex workers. We really wanted to have a transformative effect, where we worked together to co-create knowledge. Not only academic knowledge but also knowledge that is accessible to the community, and have a long-term effect with the community, that it is sustainable.

How it was to work with different communities in South Africa? This is a very diverse country, how it was for you to navigate this complexity, especially with communities that have been historically marginalized?

It was difficult! Ethnicization and intersections around race, class and sexuality are rife. There are these elements of separation strongly rooted in modernity and coloniality. With that awareness that this is really the roots of this separation if framed, I go in with the aim to push against that, however small. For me, one element that I always go to is the notion of Ubuntu, which is an indigenous way of life and being on the African continent. I remember growing up and hearing my grandma saying: that person has Ubuntu. In my mother language is: Oyo alina obuntu bulamu – meaning that person has or practices Ubuntu. They have Ubuntu, they practice the notion of Ubuntu. This is not seeing yourself as an individual in this society that separate us, but rather being in a community. That is my departing point towards work, I seek participatory and engaging practices in my research, I make sure I have time. I spent a year in South Africa. The Grace project was generous around time, and this gave us the opportunity to really connect and work together.

Can you tell me how you dialogue and exemplify Ubuntu with your students, but also with different communities?

That is the thing, Ubuntu is not a dialogue, it is a doing! I think that is what differentiates indigenous knowledge from Western ideas that knowledge has to be spoken and articulated. The embodied aspect is less appreciated. There has been a lot written about Ubuntu in philosophy and theology, and in South Africa was nationalized during the Truth and Reconciliation process, the transitional justice that took place immediately after apartheid. Desmond Tutu, who sadly passed away last December, really brought it to a central stage by appealing to the humanness during this really difficult moment in South Africa, from such a violent system to democratization. He call for humanness in the justice process.

Those who theorize and write about Ubuntu, such as Alexis Kagame [1] and John Mbiti[2], one is a theologist and philosopher, wrote that ‘a person is a person through persons’, which is the same notion I was referring to as my grandma was saying. You are a person within a community. In South Africa, in isiXHosa you say: Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (in Sesotho, it is: Motho ke motho ka batho); that means a person is a person through other persons. This breaks from the neoliberal and capitalist individualism that locates us as an individual who must achieve everything alone, but rather you exist because of you are part of a community. So if you get an achievement, you celebrate it as a community! And you also take care of a holistic view of viewing the world where community includes your environment. You are cognize of exploitation of the environment for instance, you take care of animals, plants, soil, you name it.

That is putting Ubuntu in words but it’s really about living it and being it, opposite to verbalize it. Ubuntu is lived, in the way you do, in the way you behave, in the way you interact with those around you and your environment.

How can we live Ubuntu through our relations with colleagues, with students, with cleaning service and security guards? How can we do Ubuntu within the academic community? Especially as academia can feel very lonely and individualistic

Well, that’s a million dollar question! This capitalist institutions have an individualistic agenda, but I think it takes the work of people like you and me who really do and embrace these kinds of knowledges to push away at these massive institutions that only look at the individual. As I mentioned, I was very active at the Black Academic Caucus (BAC) . I was the chair at one point, because I was so energetic about the ‘do’ and change! For me that was a space that at times brought several elements of coalition and network building with students, colleagues, also with unskilled labour and those whom institutions don’t see.

It is also in the way you do research. In the Global Grace project the kind of writing and the way we engaged with communities are also examples of these micro elements that chip away and slowly filter in the system. I’m not sure whether the university as this capitalist institution would ever fully turn, but there is space to push away for change. That is a way to do it.

But I do get your sense of loneliness. For me being in a space like South Africa where there was a common cause to fight for and understanding of that Ubuntu way of life gave me company and a community. And another way is to connect with people, I still have my South African family for when I feel alone and isolated in Essex. I know I have a South African network that is still with me in this process.

In relation to this micro elements, there is the element of joy. How does enjoyment play a role in communities that are often portrait as marginalized? And also, what is the role of enjoyment for you, as an academic?

I work with people on the margins. Street based sex workers are seen as one of the most marginalized groups in South Africa, so you could question how joy could be framed for somebody who has been constantly marginalized and has been living under a bridge for the last twenty years. And yet, there has been several moments of joy that manifested in several ways.

Perhaps I can start with the most recent one, where I got messages from the group telling me: we miss you! Come back! I was so overwhelmed by emotions, I actually wept with joy! For three years I worked with this group of sex workers, and we navigated difficult spaces, existences, ways of being together. Before I left South Africa we had a retreat to celebrate the closing of the project together. We had a plan of the whole weekend, looking back on how the project started, what we had in mind, then the middle, all the way to the end. It was very interesting to reflect, because having good intentions when working with marginality is not enough. If you are not critical, you may end up being complicit and re-asserting power.

That was a really joyful moment to reflect together as a group, in terms of where we started, how we met each other, even how they as sex workers worked together. The theatre processes helped to create a family in itself, we became a different kind of kin, we are family. Their speech to me was absolutely amazing! They put me out there in the middle of the room and they started to talk about me for an hour! It was so touching! I was weeping! They gave me a big card with all of them writing on it, and scarves for a gift, they know I love scarves!

And along the way, there were so many elements. The theatre processes themselves were at times very difficult because we were digging knowledges that were hidden, and because of the theatre processes they came out. At times it was really difficult. But performing their stories on stage made me really proud, and after each performance we would go back stage and hold ourselves and say “well done! You did it!” Even if there were difficult moments, we also laughed so many times, on the stairs of the theatre space where we used to perform, we ate together on those stairs many times. We had many moments of laughter… and crying, and fighting, and explosions. Everything!

Elsewhere I theorize around decolonial joy which is a concept from Frances Negrón-Muntaner[3], a Puerto Rican scholar with who was also connected to the Global Grace Project. Through her work in Puerto Rico theorizes that through coloniality there are all these processes and rules around you that inform your being, but then decolonial joy becomes this imagined space or moment of existence where those coloniality processes don’t inform your existence in that moment. And for the Global Grace project that resonated well, because in all the countries coloniality manifest in many forms, but for sex workers in South Africa coloniality is a lot more sharper in terms of its deployment of their marginality.

The sex workers were on stage, performing, and putting their lives on stage, really harsh lives, because sex work is so stigmatized in South Africa, beyond criminalization. However, when they were seen on stage, they became human. The stereotype of who is a sex worker disappear in that moment, you see this body in front of you performing, in that moment you see wholeness, which is an element related to what some decolonial scholars talk about re-membering. In other words, there were no segmented bodies, but whole bodies, and we needed to remember that. That wholeness was an expression of decolonial joy, where for a moment, we get to see sex workers as human those who have been constantly dehumanized.

We can close with more details about the Global Grace Project, so our listeners/reading can find more details.

The Global Grace Project was a multinational project that employed artistic methodologies as a way of investigating gender and cultures of (in)equality. There were six countries involved, South Africa being part of them, along with Bangladesh, Brazil, Mexico, the Philippines and the United Kingdom. In the case of South Africa we worked with a group of sex workers and used theatre methodologies to investigate gender and cultures of inequality. Bangladesh focused on female construction workers and worked with film and photography as the methodology. Brazil worked with decolonizing knowledge and worked with dance and theatre methodologies. The Philippines worked with the young gay community and worked with spoken word as the methodology. Mexico worked with indigenous migrants, mostly female migrants, and worked with a moving museum that took the narratives of disappearing women and indigenous migrants in Mexico. The UK brought us together, curating the different work packages, and also investigated black women in leadership positions in museums in the UK.

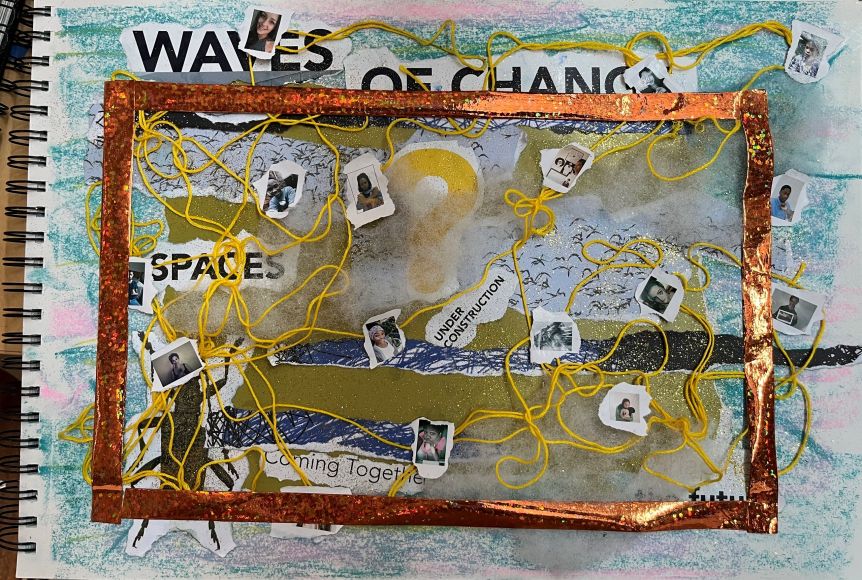

It was a project funded by the UK Research Council and we proposed several output that were artistic. One of them being the Global Museum of Equality which we launched last week Friday. It is now online. That link shows exhibitions from all the countries. This was meant to be live/in person in South Africa, but because of COVID we moved it online. Each country has an installation, we have a documentaries made over the three years of work of each country, and also poetry and postcards curated by the UK team through exchanges with all the work packages. Secondly, we developed an online course on artistic methodologies. Each country has a specific online class that draws on all their research work. We have an introduction class, and a specialized class that goes deep into, for instance, spoken word or writing poetry. And this can be used in any classroom, at the university, NGO or communities. We tried to make it as accessible as possible. The resources that we added there are either developed throughout the project or were drawn from our project partners.

We thank Phoebe for this heart-warming and inspired interview! We are looking forward to share more content in collaboration with her. If you want to see more about the Global Grace project, check their closing event that has been broadcasted via YouTube.

References:

‘Alexis Kagame - Google Académico’. Accessed 25 February 2022.

‘Decolonial Joy | Theorising from the Art of Valor y Cambio | Frances N’. Accessed 25 February 2022.

Mbiti, John S. ‘African Religions and Philosophies’. Philosophy East and West 22, no. 3 (1972).

[1] ‘Alexis Kagame - Google Académico’. Accessed 25 February 2022.

[2] John S. Mbiti, ‘African Religions and Philosophies’, Philosophy East and West 22, no. 3 (1972).

[3] ‘Decolonial Joy | Theorising from the Art of Valor y Cambio | Frances N’. Accessed 25 February 2022.