I have always found it fascinating how decisions can unexpectedly lead us to new people, situations and places. No matter how minor some of these encounters might look, they can activate infinite possibilities and journeys. It is only a matter of expecting the unexpected and being open to it.

As Hannah Arendt would say, to begin at the beginning is an act of memory and gratitude.

Joanna Vecchiarelli Scott

in Arendt, Scott, Stark, & Aurelius (1996)

I am curious about the anatomy of moments. I want to know about the make-up of the elements that form stories and chapters in people’s lives. My curiosity has grown as I have become more aware of how my life journey has shaped who I am today. My journey began in Uruguay, where I was born, when I moved from an agrarian, conservative, Catholic community to Montevideo, the liberal and vibrant capital of the country. Ten years later, amid an economic default and the worst unemployment crisis in Uruguayan history, I emigrated to Ireland, where I lived for 13 years. While in Celtic lands, I was able to take advantage of two opportunities: going back to my ancestral roots in Italy and doing a master’s degree in the Netherlands. Five years after finishing my postgraduate studies, I returned to the Netherlands, and now, the metaphor of chapters fits my situation perfectly. I am in the latter stages of my PhD trajectory. Everything seems to be about writing and finalizing the chapters of my doctoral dissertation. How did the chapter of my life that includes my research, intrinsically related to my PhD, start? What is the very moment in which I become enamoured, compelled and, without realizing it, self-assured enough to take this journey? I am not talking about why I wanted to do a PhD but rather the very moment I met the topic and entered the field that I have embraced, loved and incorporated to such an extent that it has become a symbiotic part of my life. Until recently, I thought asking and answering this question was a personal exploration and not worth sharing publicly. To a certain extent, I still believe that. However, PhD trajectories tell us who scholars are as humans, what they want to say, where they want to go, and in doing so, they inspire future generations, as many such trajectories have inspired me. The most touching example for me is Hannah Arendt’s, as told in her biography written by Elizabeth Young-Bruehl (2004), one of her doctoral students. Arendt’s biography has one of the most beautiful titles I have ever seen, For the Love of the World, which was inspired by her doctoral dissertation on Love and St Augustine. Arendt’s dissertation manuscript was so dear to her that she took it with her when fleeing Nazi Germany. There she was, in the rawest moment of her life, embracing her dissertation manuscript. What is more, Arendt continued working on that manuscript later in life, intending to expand her ideas and publish them. At the time of her death, she was still re-reading and studying the work she had completed 50 years earlier. She was still busy with her PhD dissertation.

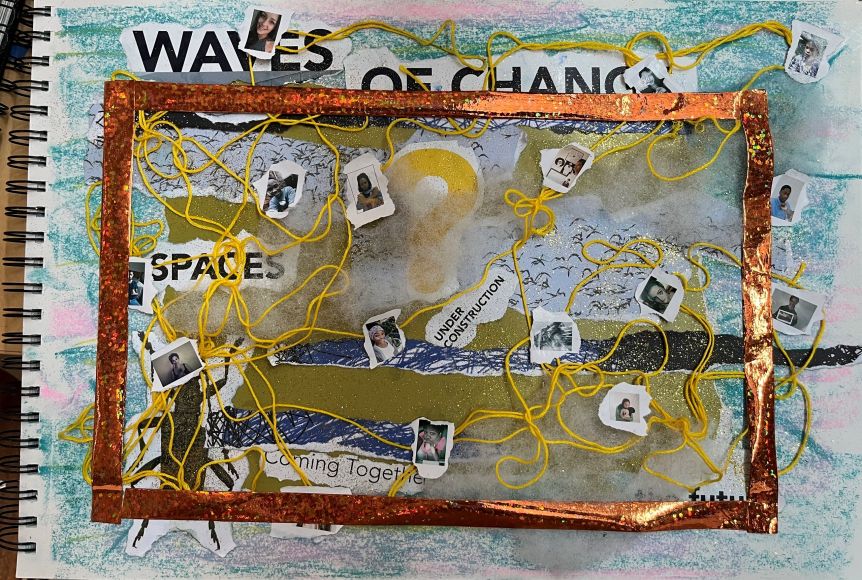

PhD trajectories are as diverse as the individuals who go through them. My research journey has countless rich and endearing memories. Some of these memories are evident and logical, like journal publications, congresses and collaborations. Other memories are more private, like taking a break from fieldwork, being inspired by someone or experiencing the surprise of having a publication quoted in a journal that had previously rejected publishing that article. As in life itself, many memories and experiences fade into oblivion. Yet, among that vast sea of names, moments and feelings, I am fortunate to remember the very moment and place when I “was born into my field”. The serendipitous moment lasted a whole afternoon: Sunday, the 11th of September 2011, between 13.30 and 19.00 hours in the (now gone) asylum seeker centre (AZC) in Crailo, a village fifteen kilometres from Amsterdam. It was the tenth anniversary of the haunting events of the World Trade Centre attacks. A new connection in the Netherlands, with whom I had exchanged ideas about diversity, migration and integration, had invited me to join him in the centre, where individuals from an NGO, former refugees, and their families and friends had organized a festival for that afternoon. The activities were conceived with a counter-discourse perspective. The festival’s central goal was to give an alternative voice and space to asylum seekers and present a critique of AZCs’ secluded locations. There was a theatre performance, live music, workshops, food, tours of the facilities and discussions chaired by scholars and activists. The emailed invitation explained, “Through this meeting, we hope to bring people who are far from each other closer together through stories. We also hope that the stories we hear will be passed on to make the greatest possible journey.”

The asylum-seeker centre, the refugees and the in-between people

Sunday, 11 September 2011, was a mild late-summer afternoon. The leafy district of Crailo was showing its best colours as the sun shone brightly through the green leaves of the linden trees. Our car stopped at the entrance to the AZC, and we showed our identity cards to the security guard before entering the grounds. I vividly remember seeing many non-residents of the centre as we approached the buildings where the main festival activities would take place. The feeling was very festive, with people coming and going, tables and chairs being moved, lists being checked, balloons being inflated. It felt like arriving at a child’s birthday party. Indeed, there were children everywhere! The warm late-summer afternoon was full of the sounds of people talking, children running, and someone testing the sound systems. The cakes, balloons, handwritten signs, and different styles of clothes that people were wearing set the whole afternoon’s colour scheme. Later, the smell of coal fire and barbeque mingled with the sounds of guitars and drums.

I do not remember what I expected or imagined the AZC would be like, but I recall seeing young men, women and children walking everywhere. I remember their faces. Some were happy and full of energy, others more pensive and submerged in clouds of thought or worry. It was not easy for me to make sense of what was going on. Were they worried about their past, their present or their future? Was there any future? Processing the information and the new stimuli kept me thinking and asking questions. Who were they? Where did they come from? What were their stories? How did they end up in the Netherlands? Are they going to be able to stay in the country? For me, they were prisoners in an invisible jail — a jail made of uncertainty, lack of structure and lots of idle time. It was the combination of invisibility and impossibility that haunted me. Yet, the festival and those who were part of it provided some solace to my concerns.

Besides the centre’s residents, the festival crowd included the organizers and those who had been invited to join. Many who attended are active in-between: that is, they work between refugees and mainstream Dutch society. In many cases, in-between individuals are former refugees or volunteers working for social initiatives that assist refugees through their journey. Like a bridge, they are between two worlds. They are a link between refugees’ past and their present and future. I have talked with many in-between individuals and have seen how they are entangled because they are committed to welcoming migrants or because they or someone in their immediate surroundings (i.e., parent, partner, friend, colleague) has a refugee or migrant background. Since that afternoon, I have seen how in-between individuals are entangled with very diverse dynamics. They are a hub that connects all the layers encompassing the problems of refugee reception and integration arising from the social and political contexts of their location. They are immersed in material and discursive structures that they constantly, consciously and unconsciously challenge and handle. That Sunday I was one of them. I was part of a collective that I did not know, that I did not understand, that I did not dare to interrogate: Why were they there? Why were they putting so much time into this activity? Why did they bring their friends, partners or family? I did not know, yet being there felt like the only place in the world to be. I knew I was in the right place, but I did not fully understand why.

The moment I was born into my field, my natality

Once again, I bring Hannah Arendt to help me unpack this experience. I discuss the notion of being born into my field by referring to Arendt’s “natality”, a concept she introduces in The Human Condition (1957). She refers to natality as the moment when an individual is born into the political. For Arendt, the political is “a way of being together, based on the principles of equality and nonviolence, in which people decide what to do and how to live together through mutual persuasion and common deliberation on matters of public concern” (p.70). In Uruguay and during broad Latin American debates, I was concerned about social justice and inclusion. However, this was the first time I had encountered the social issues of refugees. For me, that afternoon was a very political momentone that exposed issues of forced migration, secluded spaces and social exclusion. It was a moment when many then-unknown individuals, circumstances and issues of public concern came into my life and have since remained a part of who I am and what I do.

When referring to natality, Arendt uses the notion of rebirth, a period of new life, growth and renewal, to describe the moment before the action, the moment when things are done.

Action has the closest connection with the human condition of natality; the new beginning inherent in birth can make itself felt in the world only because the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew, that is, of acting. (Arendt, 1957, p.9)

With word and deed, we insert ourselves into the human world, and this insertion is like a second birth, in which we confirm and take upon ourselves the naked fact of our physical appearance […]. This insertion is not forced upon us by necessity […] its impulse springs from the beginning which came into this world when we were born and to which we respond by beginning something new on our initiative. (Arendt, 1957, p.176–177)

Through natality, individuals can make space and somehow stop time to find cracks in apparently finished walls. Through our actions, we become a part of debates: we join a network, open up alternatives and create new things by the simple fact of being and doing. Arendt refers to the naked fact, something that offers the bare, plain truth, the most primal unit of understanding, which individuals can build on. What appeals to me about Arendt’s natality is the possibility that each individual can bring new, radical and unique things into the world and the reassurance that we live to begin new things despite our mortality.

Practically ten years have passed since that late-summer afternoon. The AZC has been gone since 2016, yet the debates on refugee reception and integration have drastically amplified. I do not know what happened to the asylum seekers living in that AZC. Where are they? Were they able to get their status and find jobs to make a living and build their future? Are they happy? Do they feel welcomed? Where are those kids? They would all be teenagers now. The other people who attended the festival, the ones in-between, they became my most blatant serendipity. Because of my work in refugee reception and integration, I have crossed paths with many of them again. In pictures taken that day, I recognize many individuals who always attend activities organized by my current research group or public activities in Amsterdam or elsewhere in the Netherlands. These men and women are active members of a community that supports refugees. They currently have a decisive role in initiatives I have studied (De Vrolijkheid and Refugee Company) as well as in the Dutch Refugee Council and in different Dutch municipalities. Others are engaged volunteers and researchers. One way or the other, all of them fight for better and sustainable conditions in refugee reception, integration and inclusion.

Sunday, September 11, 2011, in Crailo was where I was born into my field: that is, “where I appear to others as others appear to me, where men exist not merely like other living or inanimate things, but to make their appearance explicitly” (Arendt, 1957 pp.198–199). The images, sounds, smells, feelings and experiences from that day have become a part of who I am. That (re)birth has since materialized into my PhD project. In this journey, I explore organizational dynamics in refugee reception and integration in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2021. I study the interplay between governmental organizations, civil society (sporadic, emergent or established) and volunteers and how they engage in refugees’ reception and inclusion. I also examine refugees’ role in the processes that claim to receive and integrate them into Dutch society. All my work is infused with the essence of that afternoon in Crailo. My project looks at voluntary work in reception centres (Larruina & Ghorashi, 2016), bottom-up initiatives during the “refugee system crisis” in 2015–2017 (Boersma et al., 2019; Larruina, Boersma & Ponzoni, 2019), possibilities for political participation at the EU level (Larruina & Ghorashi, 2020) and socioeconomic inclusion of status holders through social entrepreneurship (expected 2022).

As the organizers had hoped for in their invitation, the event in Crailo did bring people who were far from each other closer. The encounter was activated through the visible and invisible stories narrated that afternoon. Indeed, those stories were heard and passed on, as I have done, and I am doing now. I am not sure about the journeys of the other people present that day, but that mild late-summer afternoon took me on one of the greatest possible journeys of my life.

References

Arendt, H. (2018). The Human Condition: Second Edition (M. Canovan & D. Allen, Eds.). USA: University of Chicago Press.

Arendt, H., Scott, J. V., Stark, J. C., & Aurelius, A. (1996). Love and Saint Augustine. United States of America: University of Chicago Press.

Boersma F. K., Kraiukhina, A., Larruina, R., Lehota, Z., & Nury, E. A. (2019). A port in a storm: Spontaneous volunteering and grassroots movements in Amsterdam. A resilient approach to the (European) refugee crisis. Social Policy and Administration, 53, 728-742. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12407

Larruina, R. & Ghorashi, H. (2016). The normality and materiality of the dominant discourse: Voluntary work inside a Dutch asylum seeker centre. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 14(2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1131877

Larruina, R., Boersma, K., & Ponzoni, E. (2019). Responding to the Dutch asylum crisis: Implications for collaborative work between civil society and governmental organizations. Social Inclusion, 7(2), 53. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i2.1954

Larruina, R., & Ghorashi, H. (2020). Box-ticking exercise or real inclusion? Challenges of including refugees’ perspectives in EU policy. In E. M. Gozdziak, I. Main, & B. Sutter (Eds.), Europe and the Refugee Response: A Crisis of Values? (pp. 128–148). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429279317-9

Scott, J. V. (1996). Acknowledgements. In H. Arendt, J. V. Scott, J. C. Stark, & A. Aurelius, Love and Saint Augustine. (p. xix). University of Chicago Press.

Young-Bruehl, E. (2004). Hannah Arendt: For love of the world (2nd ed.). Yale University Press.

Pictures: © 2011 De Vrolijkheid. All rights reserved.